Built in 1793 by Brian Philpot and occupied by flag maker Mary Young Pickersgill from 1807 until 1857, the Flag House is the site where Mary and her household of women crafted the large 30’ x 42’ garrison flag for Fort McHenry that inspired the national anthem. In the last half of the 19th century, the Flag House’s first floor was converted into more traditional business space. It was occupied by a general store, liquor store, post office, cobbler, bank, and steamship ticket and freight office. Many of these businesses were owned by immigrants and provided services in both Italian and English. Today the Flag House interprets Mary’s life as a female business and landowner. Both archaeological digs were conducted to discover more information about life in the Flag House, the home’s role in the neighborhood as a cornerstone that joined the communities of Jonestown and Little Italy and to better understand Mary as a woman who was exceptional for her time. There is very little to document Mary’s life before or after her time in Baltimore.

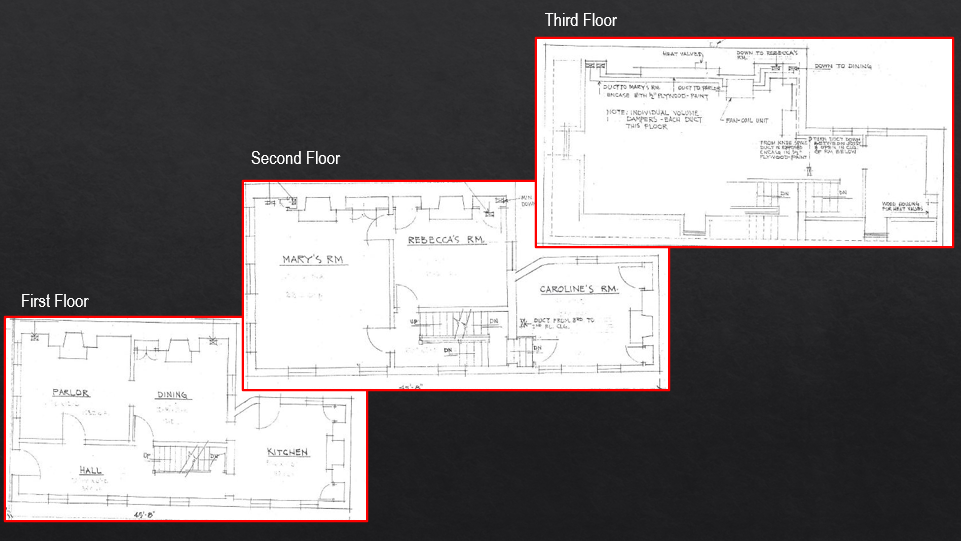

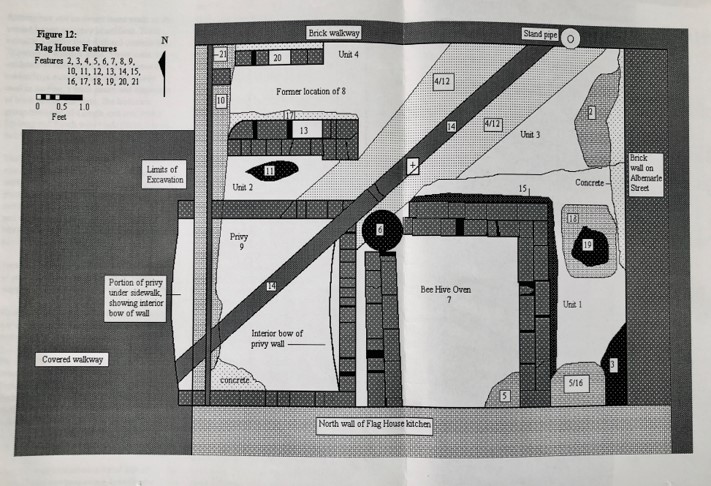

The Flag House is a two-story brick house with a third-floor attic and shared a party wall and eight-flue chimney with the building to the west on Queen Street (now Pratt Street). The kitchen wing, known as a flounder, was built at the same time as the central portion of the house. In March of 1799, two insurance policies were purchased for the home, No. 617, for the main block of rooms of the house and No. 618, which covered the kitchen. There is no mention of the beehive oven in the insurance policy for the kitchen – but because of the archaeology material located within the beehive oven foundation, we can be almost sure that it was constructed around 1807 when Mary moves into the Flag House.

In July 1807, Mary moved from Philadelphia to Baltimore after the death of her husband in 1805 to be near her mother, Rebecca, and her sister Hannah who lived a block from the Flag House on Granby Street. At this time, tensions leading up to the War of 1812 had already begun to rise, ignited by the British attack on the USS Chesapeake by the HMS Leopold and the 1807 embargo. After the War of 1812 and between 1820 and 1870, the population of Baltimore increased from 63,000 to 269,000.

By 1820, Mary Pickersgill was a homeowner having acquired half interest in the Flag House for $1,000, from the heirs of owner, Amos Vickers. On September 19, 1820, she purchased the remaining interest on the property for another $1,000. In 1828, Pratt Street was extended east and 60 Albemarle Street, the former address of the flag making business, changed to 44 Pratt.

About this same time after Mary took ownership of the house, architectural evidence suggests the Flag House’s kitchen was reworked. The beehive oven was removed in favor of an interior iron stove around 1830 (it is important to note that Mary’s son-in-law, John Purdy, was himself an iron merchant). Ghost lines in the brick of the kitchen wall indicate the location of a former opening that repeats the size of the exterior chimney base that would have allowed for a large cooking hearth and was probably associated with the beehive oven. Discontinued use of the beehive oven more than likely assisted in the preservation of the wealth of archaeological material uncovered in this survey unit.

This image from the 1955 interior restoration shows the drastically reduced size of the hearth opening.

On October 4, 1857, Mary Pickersgill died, and ownership of the Flag House passes to her daughter Caroline Pickersgill Purdy. Caroline Pickersgill Purdy leases the Flag House in May of 1864, selling the property outright in November of that year. The property was sold again to Samuel Ready in 1869, beginning an era of dwelling and retail use. Samuel Ready’s ownership dates from 1869 to 1878. Upon Ready’s death ownership of the house, passed to the trustees of the Samuel Ready Asylum for Female Orphans. The Samuel Ready trustees hold ownership until 1927 when the Flag House Association and Baltimore City take ownership of the property to preserve its history with the intent of opening a public museum dedicated to the Star-Spangled Banner. The Flag House opened to the public as a historic house on November 11, 1928. This 1894 sketch the earliest known drawing of the Flag House is done looking toward the Albemarle Street elevation we can see a small shed has appeared at the back of the kitchen – this is the site of the 1998 dig.

The Baltimore Center for Urban Archaeology (BCUA) expected to find a high concentration of cultural material at the site of the beehive oven foundation and previously undisturbed privy, and indeed they did with over 15,000 items being uncovered.

The total excavation site was a 10’ x 7.5’ square foot section of ground with artifacts totaling 15,507. There were 4,472 in unit levels, 11,035 in features. These 11,000 + artifacts were mostly found in 3 features: a 19th-century utility trench (2,994 artifacts), the beehive oven foundation (1,703 artifacts), and the privy feature (6,076 artifacts). The remaining 942 artifacts were spread out between 18 other features.

The BCUA team identified at least five buried yard surfaces in the survey area. They dated to 1928 – 1953, with objects associated with the occupation of the Flag House by the Association, 1875 -1928, with objects related to various tenants & businesses, and three early yard areas where artifacts dated from the prehistoric era through the mid-19th century. The three early yard surfaces that included the oven foundation and privy held nearly 8,000, including those items identified as being from the period of Mary Pickersgill’s occupation. The earliest features indicate that the beehive oven was constructed after 1799 but before 1807. No trace of the shed that first appeared in the 1894 drawing was uncovered.

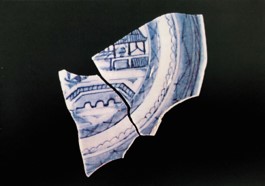

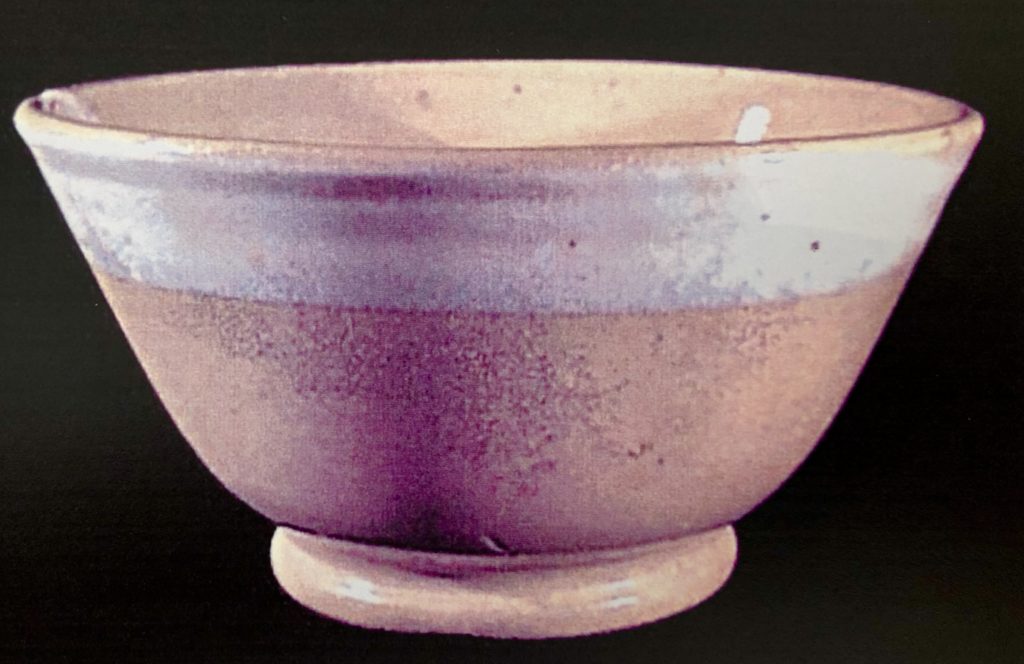

Fragments, like those pictured above, were found in one of those early yard surfaces and matched the pattern on this pierced fruit basket owned by Mary Pickersgill. They are likely remnants of the undertray for the basket pictured below.

More ceramic fragments representing utilitarian and decorative ceramics used in daily life throughout the 19th century.

Also found in the foundation of the beehive oven was evidence of the flag making business. Items included pins, thimbles, and a pair of scissors.

Objects that belonged to Mary in the Flag House Collection and artifacts uncovered during archaeology seem to indicate that Mary was a lady of refined taste, despite her socio-economic role as a widow who never remarried.

Mary advertises her flag-making business until about 1816, around the time when Caroline Pickersgill marries John Purdy. From this time until he died in 1837, John Purdy, an iron merchant, is listed as the head of the household. Despite Mary being the owner of the property, her flag making appears to cease between 1815 and 1816. Around this time in American society, genteel values of a woman’s position as wife and mother were widely accepted. In essence, Mary shows an inclination to prove she is of a true woman’s place in society through her possessions.

The Flag House interprets Mary’s life and household in this manner today. Female business operators in the 19th-century were considered less than virtuous than their contemporaries who took part in more traditional roles of child-rearing and housework. These attitudes did not seem to stop Mary from using her business success to acquire the refined furnishings and objects of material culture that would have adorned the homes of her contemporaries who may have been considered of a more genteel nature.

Part III of our Maryland Archaeology Month series, Buried Treasure of the Flag House: Immigration and Business in Jonestown, will be posted on Wednesday, April 29.

This series has been adapted from a presentation developed for the Flag House by Executive Director Amanda Shores Davis and given to the Friends of Clifton Mansion, September 2019.