Arthur Perry Sewell (1900-1946), and Elizabeth Murray Sewell (1890 – 1977), were the first curators and stewards of the Flag House. Because Arthur was blinded by a chemical attack during World War I, Elizabeth conducted all correspondence and Flag House operations alongside her husband and on his behalf. The couple resided in a third-floor apartment in the Flag House’s attic as late as 1940. Together they were responsible for the initial preservation of the Flag House, restoring it to its approximate 1813 appearance, using Works Project Administration workers, and even continuing preservation work during World War II. After Arthur’s sudden death in October 1946, Elizabeth continued as curator until April 1957. She oversaw the first initiatives to expand the museum’s footprint, including the first museum and office building (1950). In 1955, the Flag House underwent a major restoration project to restore the exterior Pratt Street facade to its approximate 1793 appearance. This phase of preservation saw the removal of the storefront window (1-3), installation of a steel beam support in the basement (4), and reconfiguring of rooms to restore partition walls and doorways removed from the first floor (5-7), brick restoration on all exterior facades (8-13) and removal of the steam heat and radiator system and plumbing in the kitchen and third-floor attic (14-16).

#ThisPlaceMatters #PreservationMonth

Posted in Uncategorized

On this #InternationalWomensDay, we’re looking back on the stories of women residents and business owners of the Flag House. During our interpretive planning research, we discovered a surprising number of women, widows, and women business owners that occupied and operated the Flag House throughout the later part of the nineteenth century. Like Mary Pickersgill before them, these women continued the tradition of utilizing the Flag House to support themselves and their families.

Caroline Pickersgill Purdy left the Flag House in 1867, beginning an era for the Flag House of residential and business use. The first post-Pickersgill woman-operated business appears in the 1868 Baltimore City Directory. Mrs. Eve Unterwagoner, a German immigrant, operates a tavern from the first floor. In the 1870 census, the recently widowed and German native Josephine Long is listed as head of household and “keeper” of a liquor store at 44 E. Pratt Street, the former address of the historic Flag House. Josephine continues to operate the liquor store until 1877. In 1878, she appeared in Baltimore City Directories as the operator of a tobacconist shop at 44 E. Pratt.

Two years later, in 1880, Mrs. Mary Hall is listed in Baltimore City Directories as the proprietor of a secondhand goods store at 44 E. Pratt and dwelling a short distance away at 55 Albemarle Street. The Flag House at this time is also occupied on the second floor by Matilda Dolman, widow age 60, her daughter Harriet Dolman, age 23, and Marguerite Cook, widow age 38. Mrs. Hall continues to sell secondhand goods from the first floor of the Flag House until 1882.

Margaret Elizabeth Bailey (nee Jones) was born in 1870 in Baltimore to Andrew Jackson Jones and Lugene Jones (nee Read) and briefly lived in the Flag House as a child. At age 20, she married Isaac Bailey (58) in Virginia. The couple returns to Maryland sometime before 1910, where they are listed in the census as residing in Chestertown, MD. After Isaac’s death at age 83, Margaret returned to Baltimore and was listed as living with her son Albion and working as a private care nurse. She lived until age 105.

Comments Off on International Women’s Day 2023

Posted in Uncategorized

The earliest record of an enslaved person residing in the Flag House can be found in the 1810 census. Their gender and age are unknown. Maryland’s enslaved population was considered taxable property, giving us varying degrees of information for those owned by Mary Pickersgill during her time at the Flag House. From 1810 and over the following fifty-five years, many more enslaved persons, some as young as 3, are listed in Mary Pickersgill’s tax records and deed to her daughter Caroline Purdy.

In 2020, the Flag House received an Institute of Museum and Library Services Inspire! Grant for Small Museums in support of a reimagining of our interpretive plan. A museum’s interpretive plan is a blueprint that guides a mission-based communication process that forges emotional and intellectual connections between the interests of the audience and the meanings inherent in the resource. Facilitating meaningful, relevant, and inclusive experiences that deepen understanding, broaden perspectives, and inspire engagement with the world around us. A small but impactful part of the interpretive planning process was conducting new research to build upon the institutional timeline. The Flag House and historian Dr. Stephen T. Whitman had already made one groundbreaking discovery when the indenture for free African American apprentice Grave Wisher was discovered in the early 2000s, challenging what was previously known about the Flag House’s residents and subverting the founders of the Flag House Association’s attempts to whitewash the history of the Flag House in their attempts to Americanize (civilize) and nationalize Baltimore’s students and immigrant population. As the interpretive planning and research process began, it was clear that the story of the Flag House and the making of the Star-Spangled Banner had been purposefully simplified in an effort to make Mary Pickersgill an American “founding-mother” figure in the early part of the twentieth century.

The team discovered 8 to 10 enslaved people living alongside free Black and white indentured persons. In an effort to rectify their previous exclusion from the Flag House’s historical narrative, these individuals are listed below, with their gender and age listed if known. Their perceived monetary worth is listed as a reminder that enslaved persons were considered property and taxable under Baltimore tax assessments.

By 1860 Baltimore’s enslaved population had dwindled to 2,218 (1,541 female; 667 male). Caroline Pickersgill Purdy was one of 1,296 Baltimore households to hold someone in slavery. Emily and Maurice were still enslaved by Caroline at the time of the emancipation of Maryland’s enslaved population in November 1864.

In the summer of 2022, volunteer researcher Jacky Shin discovered what the interpretive planning team had considered only a long shot – she located Maurice/Morris Brooks (Morris will be used from this point forward as this is the name most common in records after 1870). Born into slavery at the Flag House on February 24, 1855, to Emily (enslaved by Mary Pickersgill beginning around 1846), had remained with Caroline Purdy as late as 1870. In the 1870 census Caroline Purdy, aged 70, is listed with four other members of the household: Emily Brooks, 40, house servant; Morris Brooks, 16, M, drives wagon; Joseph Brooks, 8; and infant girl with no name, 2 months. In earlier tax assessments and the 1857 deed, Emily is listed as “mulatto.” Presuming that Emily and Morris were white-passing, it makes sense that they are listed as such in the 1870 census, and it stands to reason that up until this point, they have been overlooked. But it seems clear that these are the same Emily and Morris enslaved by Pickersgill and Purdy before emancipation.

Throughout the late 19th century and into the 20th, the Brooks family have close ties with the Poppleton neighborhood and Sarah Ann Street, home to working-class African Americans throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Morris and possibly Joseph appears to have been employed by political boss Joe Kelly, a saloon owner, and staunch anti-prohibitionist.

In 1878, Morris Brooks, driver, and Joseph Brooks, laborer, living at 86, Harmony Lane. In 1880 Morris Brooks, a driver is living at 84 Harmony Lane with his wife, Hannah, laundress, and Joseph Brooks, driver. The two brothers stay close to each other their whole lives. According to the 1880 census, Morris Brooks, 23, M, B, laborer, is living with his wife Hannah, 19, F, B, keeping house; Joseph, 18, M, B, laborer; and Emma, 48, F, B, mother, washerwoman (widowed).

In the 1890 directory, Morris Brooks, laborer, and Joseph J. Brooks, waiter, are listed as living at 934 Sarah Ann. In 1892 Emily and Joseph were living at 1110 N Parish, and Morris, Laborer at 919 Sarah Ann. In 1898 Morris Brooks, a driver is at 1113 Sarah Ann. In 1901 he was living at 222 n Carlton, and Joseph is living at 1109 Sarah Ann. In 1905 both brothers were arrested; they are involved in an altercation over politics. According to the police report, Joseph is 42 and a laborer; Morris is 51 and a laborer; both are married. Joseph and Morris Brooks are described in The Baltimore Sun (reporting on their arrest) as living at 313 North Poppleton Street.

Morris Brooks and his brother Joseph Brooks are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, a historically Black cemetery in east Baltimore.

From Resurrecting Mount Auburn Cemetery:

Located in the Westport/Mount Winans community of Baltimore, Mount Auburn Cemetery is one of the city’s largest African American cemeteries. Founded in 1872 by Reverend James Peck, the cemetery is the final resting place for former slaves, clergymen, teachers, doctors, military veterans, and Civil Rights leaders, as well as countless African-American families.

Notable burials include:

Over the years, the cemetery suffered from periods of neglect and vandalism. Articles and photographs published in the Afro-American revealed the deteriorating condition of the cemetery. Dense, overgrown briars prevented family members from locating the graves of loved ones. In October 1944, the Afro-American reported that “The graves themselves present a contrast of raw clay mounds, sunken pits, muddy trenches and weedy plots above which the marble and granite markers made a desperate effort toward dignity.” Periodically, volunteers attempted to clear dense brush and mow the grass, but maintaining a cemetery is a year-round, expensive endeavor – reportedly costing $25,000 per year – and the cemetery lacks a perpetual care fund. Without a regular maintenance plan, the landscape quickly became overgrown and weed-choked once again.

Recently, access to the cemetery has been made possible through the efforts of the inmates participating in the state prison system’s Public Safety Works program. Thanks to their hard work clearing debris, cutting down overgrown brush, and mowing grass, families are now able to visit the graves of loved ones. The worn boundary wall has been replaced with new fencing, and a new arch adorns the entrance on Waterview Avenue.

For more information about Mount Auburn Cemetery, a listing of burials, and information about the Lost Neighborhoods Project, visit – Maryland State Archives, Lost Neighborhoods Project, Resurrecting Mount Auburn Cemetery, http://mountauburn.msa.maryland.gov/

Posted in Uncategorized

This year, the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House is pleased to recognize the 2022 Flag House Scholar Award runners-up. This year’s essay contest asked seniors to write a 350-word essay recognizing a woman who exemplifies the characteristics of entrepreneurship, courage, resourcefulness, and intelligence.

Student entries recognized both famous and nonfamous women who have had significant impacts on the students’ lives and in the fields of media, literature, science, cosmetics, and medicine. The below essays scored the highest of the 28 competitive essay submissions from 14 of Maryland’s 23 counties. If you haven’t already, check out the video of 2022 Scholar Award winner Carina Guo.

Cultivator of gardens and exemplifier of worlds, Georgia O’Keefe painted the natural world as it needed to be seen, turning the tables against the dreary, reflective work that sprang up in the early 20th century. O’Keeffe rose from the dust of Wisconsin into the steely confines of New York City where she attended art school for a short period of time. Cold, looming buildings blocked out the wilderness, but the burgeoning energy and new ideas of the city impassioned her to create.

Largely passed over by her peers, O’Keeffe is best known for her towering flowers. Huge, exuberant flowers blossomed on the canvases, inciting exciting debates throughout the United States. Was it erotic? Religious? Her presence as an up-and-coming female artist in the 1920s meant that O’Keefe and her flowers would be scrutinized without mercy; the critics ignoring the dichotomy of female (and flora) in favor of pinpointing an unwavering definition on them both.

Nevertheless, she grew. She grew out of the city, moving away to New Mexico. She grew out of her flowers, leaving them for the critics and socialites to psychoanalyze and ponder. She grew into the wholeness that was dampened in New York, letting the land, weather, and flora and fauna combine with her magnifying creativity and became greater than the sum of its parts.

She painted beauty where others saw death. There was no evil in the sun-bleached skulls of cattle and coyote, and the hills that traced the horizon kept her company. Throughout the turmoil of the early 1900s, O’Keeffe observed and ignored the conventional beauties of America in preference of the desert because “it is vast and empty and untouchable – and knows no kindness with all its beauty.” (O’Keeffe)

The social restrictions on women were non-negotiables as other arts – the movies, radio, and most art – told us. Defiantly, she lived independently, painted independently, and rose to fame (however posthumously) independently. Reverence for the inanimate and useless reimagined what it meant to be a female artist in the 20th century and cemented her place in the list of artists that changed art.

The famous businesswoman and seamstress, Mary Pickersgill exemplified the traits of perseverance, creativity, and loyalty that my great-great-aunt Dorothy Bergner exhibited. Dorothy was born September 22, 1898, and died July 30, 1984. Although I never met her, my family has told stories of her peculiar yet inventive aura she exemplified when she was alive. She never married and never had any children, but instead dedicated her time and efforts to her research. She was an active cytogeneticist and researcher who specialized in plant life. Her career spanned many years and she worked at the same laboratory that many other pioneers in the field of biology would conduct research in. This laboratory was the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in upstate New York. During the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, this lab would harbor some of the greatest breakthroughs in science.

Dorothy’s involvement and research during this revolutionary time was such as an exciting and fascinating part of my family’s history that I had discovered. Her academic success was apparent as she attended Columbia University for her master’s and doctoral degrees in biology. For this time, there would have been a great deal of uncertainty and job security for women in the male-predominant field of biology. However, because of her determination and witty nature she was able to help pave the way for a new generation of female scientists who would bring a new perspective to the table. Mary Pickersgill was able to bring her perspective to the forefront through the women’s rights movement and she too faced similar backlash and uncertainty as did my great-great-aunt. Even though Dorothy has never been in textbooks and documentaries like many of the other scientists of her era, she still holds a place in history as a contributor to the field of genetics and modern science.

For centuries, women of all races have been defying systemic barriers. In the same way that Mary Young Pickersgill took care of her family while simultaneously leading a female-owned business decades before the term “business woman” was socially acceptable, Maya Angelou was defying emotional and societal barriers during a time of significant racism and patriarchal restraints. Maya Angelou is another example of a strong, dedicated, and compassionate woman who was able to break through walls in order to benefit the common good.

Maya Angelou, an African American woman born in St. Louis Missouri in 1928, was an esteemed poet and activist, writing 36 books and heart wrenching poems that exposed sentiments common to the civil war era. From an early age, Angelou experienced sexual trauma and learned how to live with the pain, similar to the way Pickersgill had to move on after losing her three children and husband. Angelou found solace in the power of literature and was able to go on to create some of the most renowned pieces to date. She moved people through words of liberation and echoed the voices of other strong black leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Mary Angelou used her voice and strong mind in Africa when she worked at the University of Ghana. She worked as a freelance writer, editor, and even joined an activist community while she was there. Her words, recited by amazing leaders like Nelson Mendela, have traveled through time, similar to the contributions that Mary Pickersgill made towards our country. Other influential figures have quoted Angelou, including Serena Williams and Tupac, proving that her message of perseverance against outstanding odds spread far and wide. She was even able to recite her poem “And Still I Rise” at Bill Clinton’s inauguration in 1993.

This world needs women like Angelou and Pickersgill, trailblazers, to set standards for excellence and perseverance. In a time where women were less than, Pickersgill proved they were more. In a time where black women were suffocated from every corner of society, Angelou proved they rise “just like moons and like suns.”

Posted in Uncategorized

March 5, 1906, Mrs. Ruthella Mory Bibbins, a “recent fellow in history at Bryn Mawr College,” gave a lecture for the Women’s College (now Goucher) on “The Federal History of Baltimore and its Memorials.” The lecture included a description of the house where Mary Pickersgill made the Star-Spangled Banner. Later that month, as part of a Goucher College course for teachers on environmental studies, Ruthella Bibbins takes 100 teachers around Baltimore to historic sites, including “Mrs. Pickersgill’s house.” (Baltimore Sun, March 13, 1906) On July 15, 1907, Ruthella called for the house’s preservation after the Star-Spangled Banner flag’s donation to the Smithsonian. Thus begins Ruthella and Dr. Arthur B. Bibbins’ fascination with the Flag House and their attempts to save the house to establish a historic site.

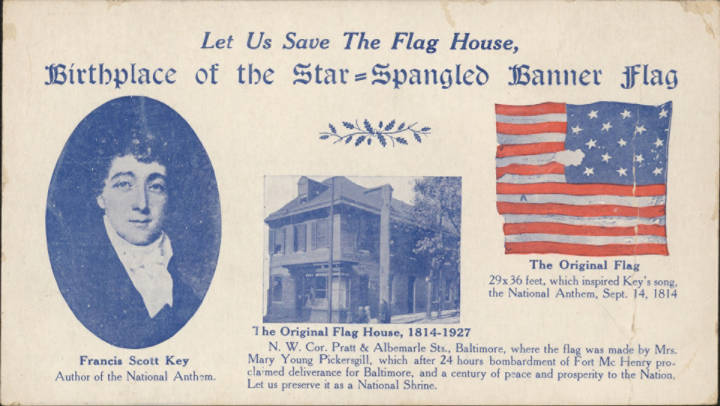

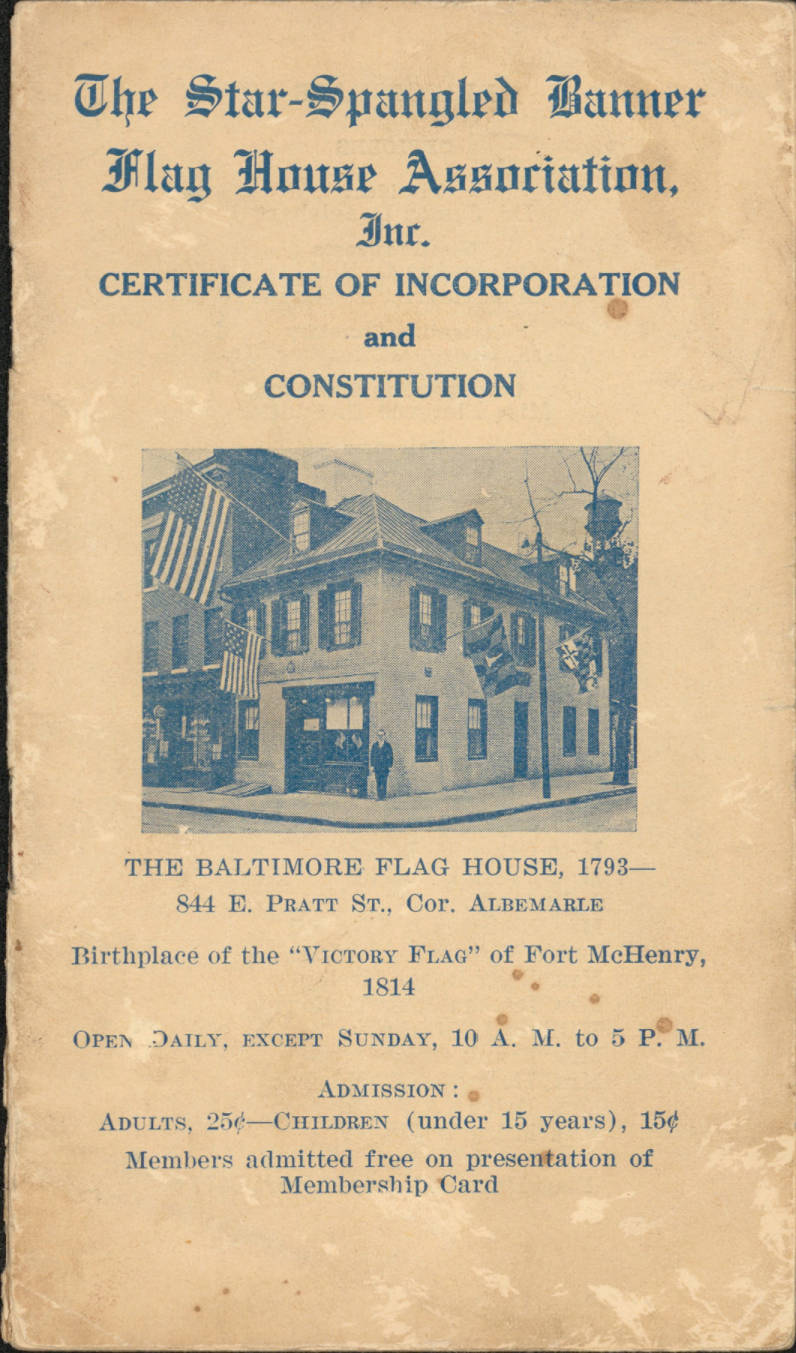

Seven years later, Dr. Bibbins serves as executive chairman of the 1914 National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial, identifying the acquisition of the Flag House as one of its projects, but it does not come to fruition. At this time, the house is the residence and business of Placido Milio, an Italian immigrant and pharmacist who becomes heavily involved in the Sons of Little Italy, acting as an immigration agent and operating a steamship ticket office, and Bank of Naples from the first floor of the Flag House. Once again in 1922, Dr. Bibbins calls for the saving of the Flag House as a place to Americanize people and the Evening Sun reports that it is “the last of the projects planned at the time of the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial in 1914, and the only one not yet carried out.” (Baltimore Evening Sun, October 21, 1922) It was not until 1927 that a campaign was launched to raise money to purchase the Flag House “for patriotic purposes.” Led by Arthur and Ruthella Bibbins and endorsed by patriotic societies. The first meeting of the Flag House Fund Campain Committee was held on February 24, 1927. The Committee circulates postcards reading Let Us Save the Flag House, Birthplace of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag, in March 1927 to raise $10,000. The Committee falls short in their fundraising efforts, and Baltimore City steps in to acquire the deed to 844 E. Pratt Street for $5,000. The Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Association, Inc. was established to operate the historic property with the purpose of “custody, possessions, and management of the said property…to restore the same to the good and same condition as a public shrine.”

On November 11, 1928, the Flag House opened a museum and historic site with a public ceremony held in the front rooms of the first floor.

Mrs. Ruthella Mory Bibbins (1865-1942) and Mr. Arthur B. Bibbins (1860-1936), founders of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Association. Mr. Bibbins, a noted geologist, and Mrs. Bibbins a historian who wrote extensively on the history of Maryland and Baltimore were members of the 1914 Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Committee and started lecturing on Baltimore’s historic landmarks as a fellow at Goucher College as early as 1906. A native of Frederick County, Ruthella later lived in Baltimore City, graduating from Goucher College in 1897, then from Oxford a year later, receiving her Ph.D. in history from the University of Chicago in 1900. In 1903, she married Dr. Arthur B. Bibbins, and together they devoted time to patriotic and civic causes in Baltimore, including tours of the historic Flag House starting around 1907 and the eventual founding of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Association in 1927. On April 19, 1927, the City of Baltimore acquires deed to 844 E. Pratt for $5,000 from the board of Trustees of the Samuel Ready Asylum for Female Orphans. Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Association Inc. was chartered on the same day. Its purpose is the “custody, possession and management of the said property…to restore the same to good and same condition as a public shrine.” Ruthella and Arthur Bibbins served as founding directors of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House and purchased or secured the donation of many of the artifacts that remain in the Flag House’s possession today. The Flag House Association, founded by Ruthella and Arthur, gained non-profit status in 1931 and remains the steward organization that operates the museum and historic property for Baltimore City. Like many of the founding directors of the Flag House Association, the Bibbins’ views on nationalism and patriotic education conflict with modern ideals of inclusion and equity. These views are reflected in their published work and the founding documents of the Flag House Association, which state, “Any white person under Twenty-one years of age, having all the other qualifications of the other members, shall be eligible for membership in this Association…”. (Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Association, Inc. Articles of Incorporation, 1927). 93 years later the Flag House is working to reckon with its history of exclusion through the visitor experience, interpretation, and research of its own difficult history.

Meeting Minutes from the first meeting of the Flag House Fund Campaign Committee

February 24, 1927

201 Park Avenue, Baltimore, Maryland

The meeting minutes read – “The first meeting of the Flag House Fund Campaign Committee was called to order by Mrs. A. B. Bibbins at headquarters, 201 Park Ave. on Thursday, Feb. 24th at 2:45 P. Mrs. Bibbins gave an interesting outline of the purchase of the Flag House and her remarks were supplemented by Dr. Bibbins who had served on the Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Committee. Mr. Richard Duvall was nominated temporary chairman and Mr. Walter W. Burns, temporary secretary. The following officers were nominated and elected:

President – Dr. James D. Iglehart

Vice Presidents – Miss Florence P. Sadtler

Henry F. Baker

Dr. Edward L Waters

Recording Secretary – Miss Elizabeth Guy Davis

Corresponding Secretary – Mrs. A. B. Bibbins

Treasurer – Mr. Richard M. Duvall

Legal Advisor – Mr. John L. Sanford

It was moved and recorded that one member of each historical and patriotic society become a member of the Flag House Fun Board and the following were elected:

Mrs. Reuben Ross Holloway, Miss Grace Bouldin, Mr. Frank Quinn, Mrs. Daniel M. Garrison, Miss Harriet Marine, Mrs. Ella Byrd, Mrs. Henry Stockbridge, Mrs. John L. Alcock, Mrs. M. L. Dashiell, Mrs. William F. Pentz, Mrs. Ferdinand Focke, Miss Mary E. Waring, Miss Josephine Lants, Hon. James H. Preston, Mr. Walter W. Burns, Mr. William Tyler Page, Mr. W. Hall Harris, Mr. George L. Radcliffe, Mr. John L. Sanford, Dr. A.B. Bibbins, and Judge Walter I. Dawkins.

It was decided to ask the Board of Estimates for an appropriation at this next meeting, March 1st. There being no further business, the Committee adjourned.

E. G. D.

Let Us Save the Flag House Post Card, March 12, 1927

In order to purchase, restore, and maintain the Flag House, the Bibbinses with the support of the Save the Flag House Committee launched a fundraising campaign with the goal of raising $10,000 – $5,000 for the purchase of the house and $5,000 for maintenance. The Committee would fall short of their goal by the March 12, 1927 deadline, requiring the financial assistance of Baltimore City. The Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Association was incorporated on April 12, 1927.

Informational Booklet, 1927, The Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Association, Inc. Certificate of Incorporation and Constitution

November 11, 1928, the Flag House opens to the public as a historic house museum and shrine. Exhibits include 19th-century furnishings, Young-Pickersgill family objects, and War of 1812 artifacts, anniversary ephemera, and flags.

Back Row L to R: Dr. Arthur B. Bibbins, one of the founders and first Vice President; Mrs. Arthur B. Bibbins, one of the founders and Historian; Mrs. George E. Parker, Jr., Recording Secretary, and Mr. Walter W. Beers, Treasurer.

Second Row: Mrs. John G. H. Lilburn and Miss Grace E. Bouldin.

In the last row wearing the plaid coat is Mrs. Rosa Pirotti Milio, wife of Placido Milio with their son Louis R. Milio. Placido Milio immigrated to the United States around 1907 through Boston. Placido, a pharmacist, moved to Baltimore to work in the Flag House as a pharmacist within Dr. Giampetro’s medical dispensary. From 1908 to 1927, the Milios operated the pharmacy, Italian bank, and agency of the Adams Express Company. Mr. and Mrs. Milio were active in assisting Italian citizens with immigration to the United States, specifically to Baltimore’s Little Italy.

Arthur P. Sewell, first curator of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House stands at the southeast corner of the historic house in 1928. A veteran of World War I, Mr. Sewell suffered sight loss due to a chemical attack during the war. He and his wife, Elizabeth Murray Sewell, worked together to tackle the restoration, operation, and business affairs of the Flag House, often lecturing around the state and country for various hereditary societies and military groups. As newlyweds in 1928, the Sewells lived on the third floor of the historic Flag House. The couple resided in a third-floor apartment in the Flag House’s attic as late as 1940. Together Arthur and Elizabeth were responsible for the initial preservation of the Flag House restoring it to its approximate 1813 appearance and the expansion of the museum’s footprint to include the first museum and office building (1950). After Arthur’s sudden death in October of 1946, Elizabeth continued on as curator until April 1957. During her tenure as curator, Elizabeth secured the donations of significant artifacts, including many furnishings for the Flag House’s early period rooms and objects related to the life of Francis Scott Key. In September 1958, she donated bound copies of curator’s reports dating back to 1927 for the Flag House archive.

Comments Off on The Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Turns 93

Posted in Uncategorized

The Star-Spangled Banner Flag House’s Executive Director Amanda Shores Davis has been awarded the Gearhart Professional Service Award from Preservation Maryland.

The Gearhart Professional Service Award is presented to an individual who is employed as a professional by a historic preservation organization, agency, or academic institution and who has demonstrated extraordinary leadership, knowledge, and creativity in the protection and preservation of Maryland’s historic buildings, neighborhoods, landscapes, and archeological sites. Nominations will be evaluated based on the impact of the person’s achievements and their contributions to the preservation of Maryland’s history and culture.

Ms. Davis has been Executive Director of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House & Museum since 2014. Davis was president of the Greater Baltimore History Alliance from 2017-2020, is the secretary of the Maryland Four Centuries Project, and serves on the Small Museum Association Conference Committee. Under Davis‘ leadership, the Flag House was awarded accreditation by the American Alliance of Museums in March 2019. Accreditation is the highest national recognition afforded the nation’s museums. Of the nation’s estimated 33,000 museums, 1,000 are currently accredited. The Flag House is one of only 23 museums accredited in Maryland.

Congratulations to Amanda and the other winners of this year’s Best of Maryland Awards! Visit the link below to learn more about the 2021 Best of Maryland Awards winners and Preservation Maryland.

Posted in Uncategorized

This year, the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House is pleased to recognize the runners up in for the 2021 Flag House Scholar Award. This year’s essay contest asked seniors to write a journal entry about their lives during the COVID-19 pandemic, creating a primary source for historians of the future.

The creative, exceptionally written, and sometimes emotionally moving journal entries below scored the highest of the 28 competitive essay submissions from 11 of Maryland’s 23 counties. If you haven’t already, check out the video of 2021 Scholar Award winner, Kaylee Kim.

3/30/2020

The initial two-week quarantine was supposed to end yesterday, and I thought we would be back in school today- I’m not mad about it though, I haven’t had homework to worry about! A stay-at-home order was just issued, the state is “no longer asking or suggesting that Marylanders stay home, [but] directing them to do so.” I’m not sure how long it will last, but I’m a little scared. Does this mean we can’t even take walks in the neighborhood? Masks are also pretty much sold out everywhere, so we’ve had to use my old Girl Scout bandanas and hair ties.

My screen time in the past month has gone up by 40%. I never thought I would be on TikTok or Netflix this much. All this extra time made me want to try something new, so I picked up baking! Well, not exactly, but I’ve made three types of microwavable mug cakes so far.

I should probably start studying for the SATs again, the next test date is April 20th- hopefully, COVID cases start going down by then.

3/21/2021

It’s been almost a year since my first journal entry. I never in my life thought I would say this, but I badly want to go back to school- goodbye Prom, graduation, senior picnic, and crab fest. What was supposed to be four of the most exciting years of my life, was cut down to two and a half.

I’ll be attending a protest against the rise in racial hate crimes at the Columbia Lakefront this Wednesday. I never thought racism was so prevalent in my own community, but I’m glad awareness is increasing. Places I visit daily, like Kung Fu Tea, were targeted. When there are so many things happening in the outside world, my mind refuses to pay attention to my Calculus teacher on the tiny computer screen.

I’m supposed to get the first dose of the vaccine this Saturday, I remember last July thinking we wouldn’t even have a vaccine until 2022. I think change is coming 🙂

Hello, my dear friend, History. Perhaps you informed us so long ago that we forgot. Or, maybe we just did not listen when you told us how a pandemic can change life as we know it. You gave us National Archives filled with examples; yet, somehow, most never considered the modern-day possibility–and then, it came.

History, you told us it could be like this. Once the World Health Organization declared a pandemic, I did not enter a public place for two months. It was three months before I saw a friend in person, but I could not hug her; I could not even see her face behind the mandatory masks. To find some opportunity for interaction, I began working. Per federal orders, this job made me an “essential” employee–at age sixteen. Approaching one-year of employment, I still have not seen my coworkers’ faces. I am one of the lucky students whose school returned to primarily in-person learning after eleven months of staring at computer monitors in isolation. Many students still wait in isolation. Sadly, hospital Emergency Department records report that some have surrendered.

Isolation, loss of loved ones, and longing for the past replaced laughing and hope for the future. Receiving cards from friends through the mail became the high point of many days, so much that I started my own organization, Cards2Care4Teens, to design and distribute cards to others who needed connection like I did.

Somehow, my dear friend, History, you knew what to do to help–-you educated and informed my other dear friend, Future. Research and innovation led to vaccines in record times; I and others now await our vaccine cards we will carry like passports to hope. Although cultural norms of handshakes and hugs temporarily have been replaced by elbow bumps and air hugs, we prepare for senior prom on a sports field. We anticipate high school graduation in-person because we allowed History and Future to work together.

My dear friends, History and Future, you taught us how to live through a pandemic. I will share your stories; lives may depend on them.

December 18, 2020

Dear Jocelyn,

I was pleasantly surprised to receive your letter in the mail today. As you said, many Americans are mailing each other because of the proposed cuts and I absolutely agree with you that we should join them. I have been reading about the benefits of the postal service on EPI lately- I had never thought about how crucial guaranteed mail service is to remote areas! – and I am inspired to help keep USPS alive. Not to mention, living in the online world of Zoom and smartphones is exhausting and I am glad to escape the screens with some pen and paper. It seems all of my friends have taken a step back these days and adopted projects like baking sourdough bread, crocheting with plastic bags to raise awareness for climate change, and learning new skills like painting from Bob Ross. I’m not a painter myself, but Ross’s calm wisdom is certainly welcome during quarantine. It is a fascinating trend that when we were forced to rely on technology for everything from school to work to fun that we returned to using our hands to bring us peace. And inner peace is something we could really use right now. I cannot forget George Floyd or Breonna Taylor and keep thinking of all the other injustice we’ll never even hear about. I want to march in D.C., but after reading in The Guardian about the 500+ instances of police tear-gassing protestors, my parents won’t let me. I know it seems like the hardships will never end, but I’m looking on the bright side. Although you are stuck at home because your sister is immunocompromised at least you are keeping her safe; although protests are scary at least BLM is speaking out for what’s right; and although online school with our families in the house seems like the nightmare that won’t end, at least we still have an education and we know our loved ones are still here. I am humbled that these things are a privilege.

We’ll beat this virus soon! Your loving cousin,

Denby

One way I chronicled time during the monotonous year of 2020 was through the evolution of my masks. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic when we as a country were unaware of the gravity of the virus, masks were only being worn by healthcare workers. My mom works in a hospital, so the only masks I saw were those she discarded in our garage trash can when she returned from work. By April, we realized our country was in it for the long haul and everyone needed to wear masks to protect themselves. Because surgical masks were sold out, and no companies had begun selling masks to the public yet, I returned to my Girl Scout roots and retrieved our sewing machine. My mom and I made fabric masks for everyone in our family. Those became our necessary, but also fashionable, accessories. As 2020 progressed, so did mask accessibility. By the summertime, it also became clear that COVID-19 was not the only threat to the lives of American citizens. I proudly wore my “Justice is Love Out Loud” mask in support of the fight against racism. As the intensity of the summertime closed, a silver lining appeared in the form of a mask modeling photoshoot a friend had recruited me to do. As a fan of the strong female characters in the American classic, Little Women, I was excited to don a mask with a quote by author, Louisa May Alcott. By the start of my senior year, we had been away from the school’s campus for six months. School was 100% virtual. Eventually, administration allowed small groups of students to visit campus and socialize. This gift of returning to school came along with a green and gold mask embossed with the school’s emblem. Now that we have in-person instruction several days a week, I continue to wear it to school. For me, it symbolizes positive change and optimism for the future of our country. I am currently on the waitlist for the COVID-19 vaccine and cannot wait for the day I can officially archive my masks.

Posted in Uncategorized

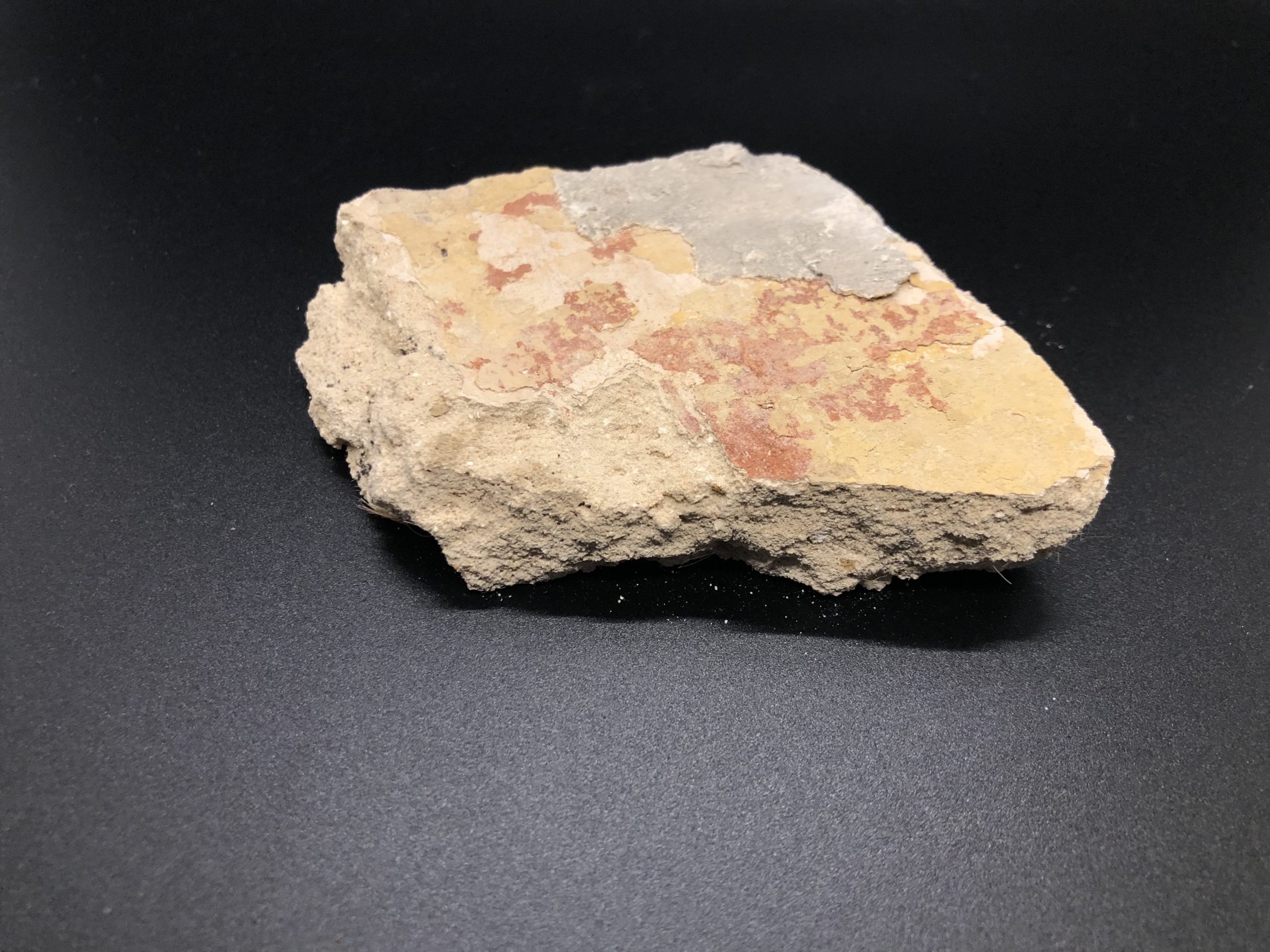

Efforts to preserve and restore the historic fabric of the Flag House began during the 1914 Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Celebration when chairpersons Arthur and Ruthella Bibbins began fundraising to purchase the open the house as a historic shrine. By 1927, the historic Flag House had been purchased with the assistance of Baltimore City, opening as a public museum in 1928. The Flag House trustees hired Arthur Perry Sewell (1900-1946) and Elizabeth Murray Sewell (1890 – 1977) as the first curators and stewards of the Flag House. Because a chemical attack had blinded Arthur during World War I, Elizabeth conducted all correspondence and Flag House operations alongside her husband and on his behalf. The couple resided in a third-floor apartment in the Flag House’s attic as late as 1940. Together they were responsible for the initial preservation of the Flag House, restoring it to its approximate 1813 appearance, using Works Project Administration workers, and even continuing preservation work during World War II. After Arthur’s sudden death in October of 1946, Elizabeth continued as curator until April 1957. She oversaw the first initiatives to expand the museum’s footprint to include the first museum and office building (1950). In 1955, the Flag House underwent a major restoration project to restore the exterior Pratt Street facade to its approximate 1793 appearance. This phase of preservation saw the removal of the storefront window installation of a steel beam support in the basement, reconfiguring of rooms to restore partition walls and doorways removed from the first floor, brick restoration on all exterior facades, and removal of the steam heat and radiator system and plumbing in the kitchen and third-floor attic.

The nails, glass, wood, and plaster below were collected during the various preservation efforts of the historic Flag House and the archeological survey conducted by the Baltimore Center for Urban Archaeology in 1998 to uncover the foundations of the nineteenth-century privy and beehive oven located directly behind the north wall of the Flag House’s kitchen.

For more #NationalPreservationMonth stories follow the National Trust for Historic Preservation @SavingPlaces, #ThisPlaceMatters & #TelltheFullAmericanStory.

Posted in Uncategorized

When spring comes, women being to exercise their minds as to what they are to wear to be in fashion and show off their charms. Everyone may wear garments of any period or non provided they have big sleeves and revers or frills on their bodices.”

– Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century, C. Willett Cunnington

As the weather warms and the colors of nature spring forth from the ground, a change in women’s dress was undertaken with much enthusiasm. Flimsy dresses in a “modified empire” style made of silk foulard, jabots of lace, and satin ribbons of heliotrope, grey, art bronze, peacock blue, grey, shards of orange, jonquil, and dull green wear taken from wardrobes to replace the velvet and wool frocks of the darker months. Some of the favorite color combinations of the women of the 1880s were browns and greens, pink with bright yellow, salmon and ruby, and cardinal and dark blue, appropriate to the feminine attitude of the day.

In the spring of 1888, the newly married Mrs. William Fletcher Pentz likely paired her custom wedding bonnet with a fine dress of grey spring-time silk adorned with touches of pinks and greens. While white was the highest fashion for wedding gowns after the 1840 nuptials of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, it was not required. Brides could still choose to wear their finest dress in a color of their choosing so that it could be worn again. Victorian etiquette did dictate that high necks and long sleeves were still the standards for daytime weddings.

By 1900, the Victorian’s hold on social etiquette of dress began to loosen. The use of gold kid for the custom evening slippers on exhibit is unusual for their date of 1900, as it was not until the 1920s that metallic leathers became common for women’s evening shoes. Objects such as this challenge our conventional view of history, and it is hard to posit for what occasion such extraordinary shoes would have been worn.

Wedding Bonnet

O’Neill Millinery and Fancy Goods, 1888

Baltimore, Maryland

This gray straw bonnet with matching ribbon, dot lace, and delicately colored flower container was worn by the donor, Mrs. Betty Houck, on her wedding day to Dr. William Fletcher Pentz, April 1888. Dr. Pentz was a member of the Maryland Legislature from 1898 until 1901. The Pentz-Trisler families were among the first donors to the Flag House’s collection and had strong familial ties to Baltimore’s defenders during the War of 1812.

Trisler-Pentz Collection of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House

FH1962.5.2, Gift of Mrs. William F. Pentz

O’Neill, Millinery & Fancy Goods

Founded in 1882 by Thomas O’Neill, O’Neill’s Department Store began as a dry goods supplier at Charles and Lexington Streets. The store and owner were well known for their specialty wares, and Thomas O’Neill’s presence at the front door at 8:30 each morning outfitted in spectacles, striped trousers, black dress coat, and his distinguished red mustache. After the department store survived the Great Fire of 1904, O’Neill purchased the entire block on the east side of Charles Street to Franklin Street, opening several other buildings. Thomas O’Neill died in 1919, bequeathing the store to its employees. The store closed in 1954 and was demolished in 1961 as part of the Charles Center urban renewal project.

Evening Slippers

c. 1900

Baltimore, Maryland

Pair of gold kid leather, evening slippers custom made and gently worn. Feature braided bows at the foot opening and a slight heel flared at the base.

Wheeler Pinchbeck Collection of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House, FH1963.2.2, Gift of Mrs. Frances Sevier

Jabot

Rose Point Lace

c. 1850

Wheeler Pinchbeck Collection of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House

FH1962.7.4, Gift of Mrs. Frances Sevier

Jabots were used to fill in the deep V necklines of women’s dress bodices.

Comments Off on Spring Comes to Baltimore

Posted in Uncategorized