There have been two significant archaeological surveys at the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House. The first survey took place between September 1998 and January 1999, intending to uncover artifacts in a privy and beehive oven foundation directly behind the historic Flag House. This project uncovered more than 15,000 unique artifacts. The second and less extensive survey was done in 2001 to determine if there were any sites of significant cultural material located within the site area demarked for construction of the Hofmeister Building, the Flag House’s modern museum facility.

Built in 1793 by Brian Philpot and occupied by flag maker Mary Young Pickersgill from 1807 until 1857, the Flag House is the site where Mary and her household of women crafted the large 30’ x 42’ garrison flag for Fort McHenry that inspired the national anthem. In the last half of the 19th century, the Flag House’s first floor was converted into more traditional business space. It was occupied by a general store, liquor store, post office, cobbler, bank, and steamship ticket and freight office. Many of these businesses were owned by immigrants, provided services in Italian and English, and are evidence of the diversity of the Jonestown neighborhood. Today the Flag House interprets Mary’s life as a female business and landowner.

Both archaeological digs were conducted to discover more information about life in the Flag House, the home’s role in the neighborhood as a cornerstone that joined the communities of Jonestown and Little Italy and to better understand Mary as a woman who was exceptional for her time. There is very little to document Mary’s life before or after her time in Baltimore. We know she was born in Philadelphia in 1776 at the height of tensions between the Americans and the British. We understand that the death of her father, William Young, in 1778 was the catalyst for Mary’s mother Rebecca turning to her brother Col. Benjamin Flower, Commissary to George Washington’s Continental Army, for assistance in launching a military supply business. We know that the same fate befell Mary when her husband John Pickersgill died suddenly while working in London in 1805, and like her mother, Mary never remarried and turned to flag making to support her daughter Caroline. And we also know that in her later life, Mary devoted her time to philanthropic ventures that aided the women of Baltimore whose lives closely paralleled her own experience. What we don’t know is how she felt about any of this. What were her tastes? How did she reconcile being a seemingly progressive woman with the rise of genteel values and societal pressure to be a respectable woman who was married, a mother, and virtuous? There are no known primary source documents in Mary’s voice. We have the receipt for the Star-Spangled Banner, the receipt for the last known flag made by Mary in 1815, and minimal records from the Impartial Female Humane Society during Mary’s presidency. The goal was to find and analyze the cultural material, personal objects, household objects, food, toys, tools, anything that might inform the previously unknown history of the Flag House and its occupants.

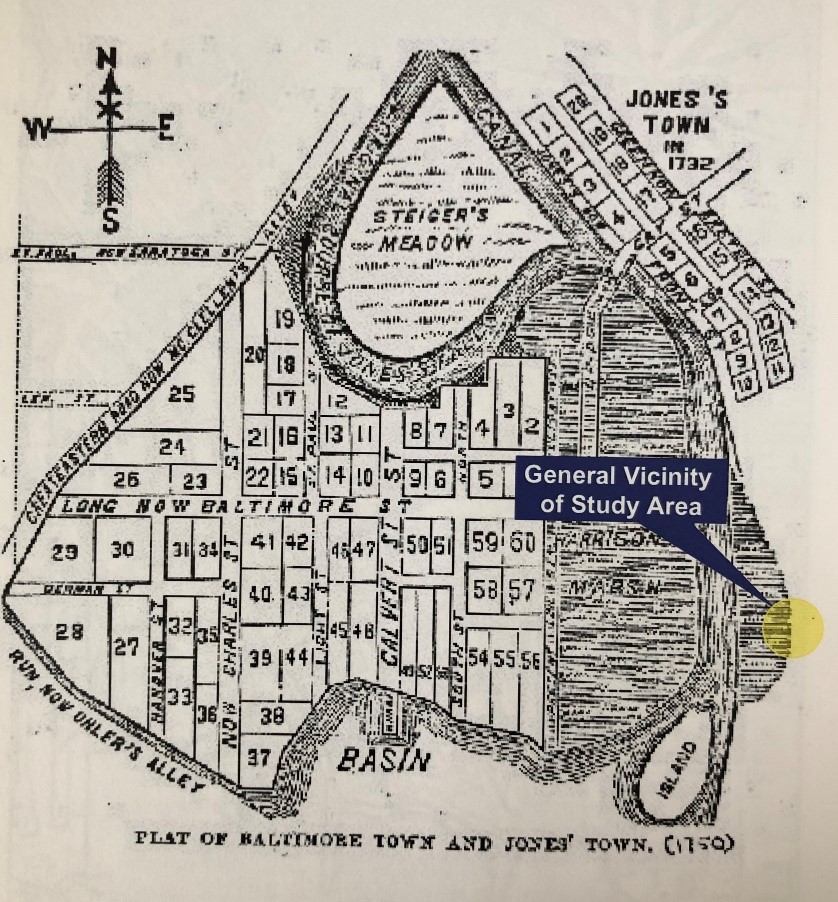

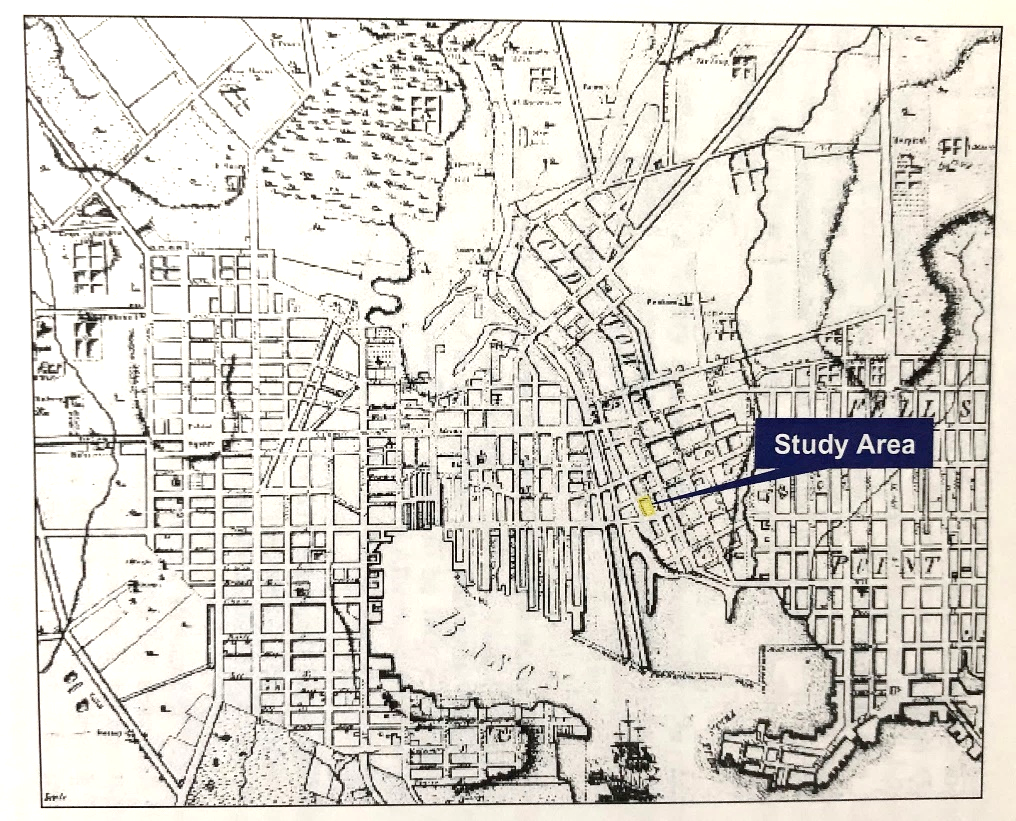

1750 Plat of Baltimore Town & Jonestown – 1998 Study Area Highlighted

To understand the significance of much of the archaeology surveys’ findings concerning the Jonestown neighborhood, we need to travel back to Baltimore’s days as tobacco farmland. The Flag House sits in the Jonestown neighborhood of Baltimore City and is considered to be the oldest neighborhood in Baltimore, tracing its development back to the late 17th century. By that time, much of the original tracts of land owned by Thomas Cole and David Jones were used for tobacco cultivation. The parcels, owned by James Todd, amounted to just over 1,100 acres in the areas of the Jones Falls and today’s Inner Harbor.

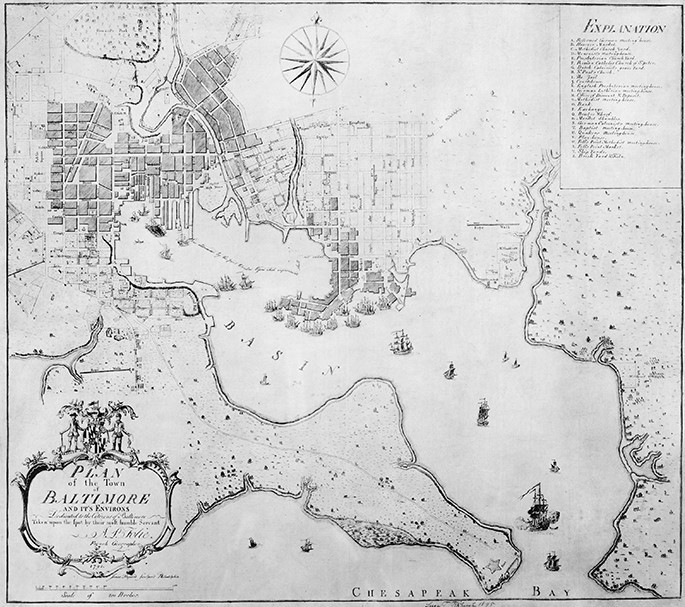

1772 A.P. Folie Plan of the Town of Baltimore & Environs

Todd began to sell his land holdings in 1701, encouraging more tobacco farming and the first grist mill on the Jones Falls to be constructed in 1711. The tobacco planters eventually petitioned the Maryland General Assembly to form a town. Thus, Baltimore Town was established on 60 acres at Coles Harbor in December of 1729. Two years later Jonestown, also known as Old Town, was laid out across from the Jones Falls from Baltimore Town.

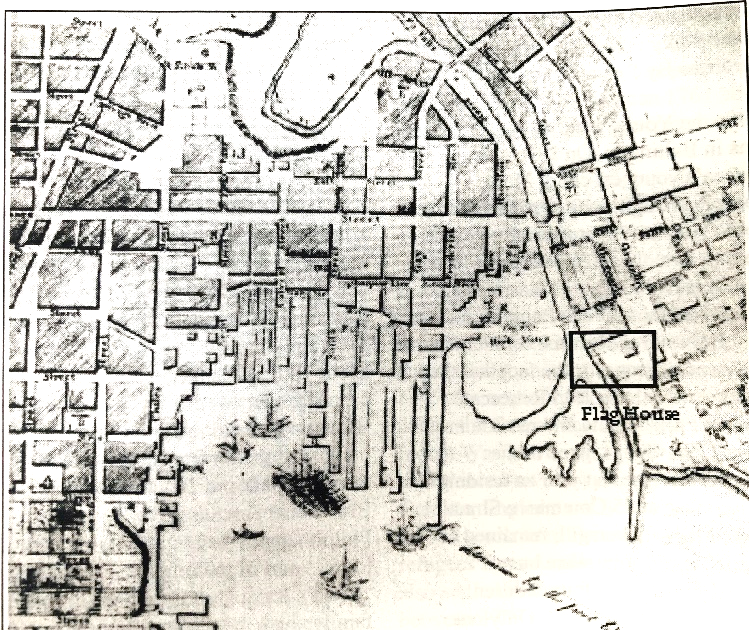

Star-Spangled Banner Flag House Collection, 2000.1.0

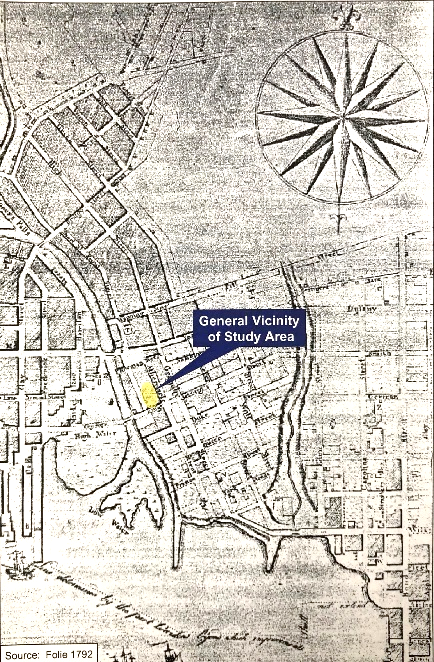

The land on which the Flag House sits was developed by Brian Philpot, whose occupation is listed as ‘gentleman,’ in 1793. That same year, with a jump in population growth, Baltimore’s merchants seized the opportunity to lobby the Maryland General Assembly to charter and incorporate Baltimore as a city; the request was granted in 1796. The land on which Brian Philpot built what would become the Flag House was part of the original Todd’s Range to the east of the Jones Falls and had been in the Philpot Family since the mid-18th century. The land had been subdivided in 1773 between Brian Philpot, Johnathan Plowman, and William Fell as additions to the City of Baltimore. This 1792 map shows the extent of development in Old Town – the Flag House lot at the corner of Queen Street (now Pratt) and Albemarle Street would be developed the following year.

1792 Plan of the Town of Baltimore & its Environs

1792 Map Detail

Jonestown, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was a fashionable area of the City. Neighbors included Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the wealthiest man in Maryland, who wintered at Carroll Mansion at Front and Lombard Streets, beginning in about 1818. But the neighborhood was also very diverse, something that continues to characterize the community until this day. Jonestown had a robust population of tradesmen that owned homes with their shops and businesses below on the ground floor. There was a: brewery, cut nail factory, spinning wheel manufactory, printer, watchmaker, jeweler, plow maker, cabinet maker, carver and gilder, and of course, a flag maker.

in all directions, and Jonestown had grown even further to the east past Central Avenue

The Flag House is a two-story brick house with a third-floor attic and shared a party wall and eight-flue chimney with the building to the west on Queen Street (now Pratt Street). The kitchen wing, known as a flounder, was built at the same time as the central portion of the house. In March of 1799, two insurance policies were purchased for the home, No. 617 for the main block of rooms of the house, and No. 618, which covered the kitchen. There is no mention of the beehive oven in the insurance policy for the kitchen – but because of the archaeology material located within the beehive oven foundation, we can be almost sure that it was constructed around 1807 when Mary takes occupancy in the Flag House.

Part II of our Maryland Archaeology Month series, Buried Treasure of the Flag House: Mary Pickersgill, will be posted Wednesday, April 15.

This series is adapted from a presentation developed for the Flag House by Executive Director Amanda Shores Davis and given to the Friends of Clifton Mansion, September 2019.