Stars, Stripes and the Unsung Woman Who Sewed Them in Baltimore

Mary Young Pickersgill’s legacy lives on in the house where she made the national anthem-inspiring Star-Spangled Banner

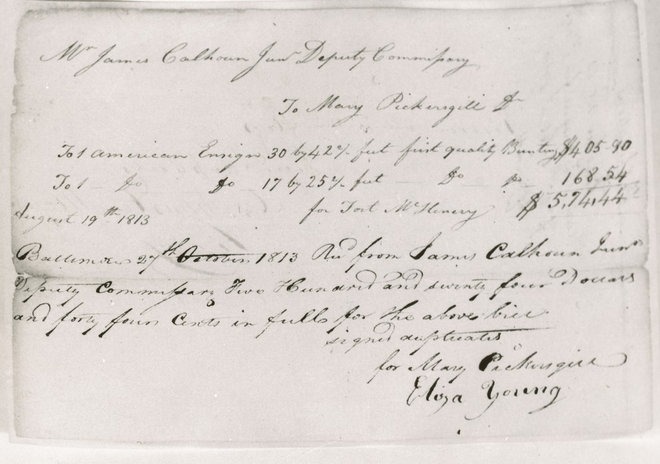

When Mary Young Pickersgill was stitching together the yards of wool bunting that would become her young nation’s famous Star-Spangled Banner in 1813, the red, white and blue fabric took up nearly the entire first floor of her Baltimore home.

The flag is “only a few inches shorter than the actual length of the house itself, so there was no way they could lay it out flat and finish placing stars and things,” says Amanda Shores Davis, executive director of the Star-Spangled Banner Flag House and Museum. “About a half-block behind where the Flag House sits is a brewery plant, so they were able to lay the flag out on the malt house floor.”

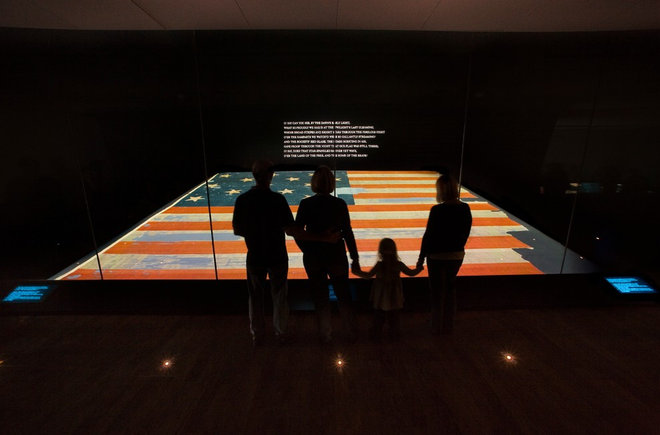

The completed 30-by-42-foot flag would later fly above nearby Fort McHenry and, during the War of 1812’s Battle of Baltimore, inspire Francis Scott Key in 1814 to write a poem about the “broad stripes and bright stars” he could see as a captive aboard a British ship. The poem would go on to become the U.S. national anthem. The flag remains one of the biggest visitor draws in the Smithsonian Institution’s Washington, D.C., collection.

Key’s name would be forever affixed to patriotic history. Pickersgill’s role in the story, however, never quite garnered the same level of national publicity.

Building a Business

Pickersgill was born, like the country itself, in Philadelphia in 1776. Her mother, Rebecca Young, ran a flag-making and military supply business throughout the Revolutionary War (contrary to popular belief, more famous flag seamstress Betsy Ross wasn’t the only woman sewing the Stars and Stripes during the conflict, Shores Davis says). Both widowed, Young and Pickersgill, along with Pickersgill’s daughter, Caroline, moved into the Federal-style brick house in Baltimore in 1807 and promptly set up a new flag-making shop.

The women were entrepreneurial and got their name out in their new market, Shores Davis says. “[Mary’s] skill was certainly known in the city, so when George Armistead, the commander at Fort McHenry, wanted to order a large flag, he knows who to go to,” she says. “Large” is something of an understatement. Armistead is said to have specifically wanted a flag “so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance,” and Pickersgill delivered with the massive 30-by-42-foot garrison banner.

Pickersgill’s contributions to 19th-century America didn’t stop with her famous flag. She was a passionate advocate for women and social justice, and later served as the president of the Impartial Female Humane Society. She fought for higher wages for seamstresses and established the first aged women’s home in Baltimore (which has changed locations but is still in operation today as the Pickersgill Retirement Community). By the 1820s, she had even purchased her own house, a rarity for an unmarried woman at the time.

“I like to think of her as probably a pretty tenacious person,” Shores Davis says.

Pickersgill lived in the house until her death at age 81 in 1857, and Caroline stayed there 10 more years. Built in 1793, the residence likely housed tenants before Young and the Pickersgills moved in, and it featured a first floor that was probably devoted to the women’s business and a second floor that served as living space.

“[The house] tells us so much about the ways in which the family lived and what it possibly could have been like for [Mary],” Shores Davis says. When Pickersgill was faced with the death of her husband, she didn’t remarry as might have been expected of her at the time, Shores Davis notes. Instead Pickersgill focused on her work and providing for her family.

“She kind of took it upon herself to be the head of household and start this successful business,” Shores Davis says. “So, you can kind of see that success through some of the objects that we display in the home. And just seeing the handsomeness of the house itself is so moving and tells us a lot about her ability to take care of a household.”

A House Full of History

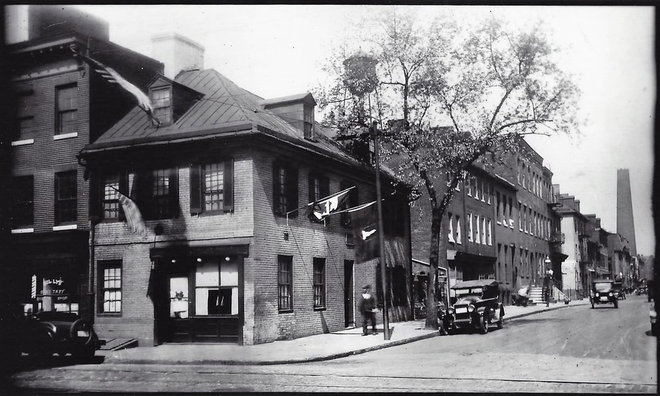

For a time after the Pickersgills lived in the house, it was a storefront post office and a general store. Businesses there were bilingual, as the house sat right across the street from where Little Italy began. It may have been a children’s home at one point.

But the place’s connection to the famous flag was always known. “In a lot of the historic photos of the house, even before it was a museum, there was a flag flying out front,” Shores Davis says. The city purchased the house in 1927 to turn it into a museum, and preservation work started on it almost immediately.

In the 1990s, archaeological work at the site uncovered more than 15,000 artifacts, including everything from modern pieces of chewing gum to historic candy dishes and earthenware bowls. Today the original house sits next to the original 1950s museum building, which has been converted into an education center, and the 2003 Hofmeister Museum Building, which features exhibition space, an orientation theater and the two-story Great Flag Window to give visitors an idea of just how massive Pickersgill’s Star-Spangled Banner really was.

Preserving the Flag

Cmdr. Armistead’s family kept the Fort McHenry flag for decades, for many years in a canvas bag in a safe deposit vault to prevent deterioration. It was given to the Smithsonian in 1912 with a wish that it always be on public display.

Teams of conservators and other specialists have put years of work and millions of dollars into its preservation, and visitors can still see it under glass in a carefully climate- and lighting-controlled case at the institution’s National Museum of American History.

This fall, the Flag House will undergo its largest preservation project since the mid-2000s. Brickwork and fences will be restored, Shores Davis says, and period replica shutters will be preserved or replaced. Work is set to be completed by the end of the year.

In the meantime, the Flag House’s programming continues to honor the property’s history and Pickersgill’s spirit. The museum granted its first Mary Pickersgill Award for Women’s Leadership in Business in 2012, and the annual prize has already recognized Baltimore women business leaders such as Johns Hopkins Hospital’s first female president, Dr. Redonda Miller, and Carla Hayden, the first African-American and first woman Librarian of Congress, among others.

“People that hear [Mary’s] story will be able to relate it in some way to their own story in business or life. Mary is the pinnacle of grit and determination. She accomplished so much in a time when it was uncommon for women to be in business,” says Nicole Sherry, head groundskeeper for the Baltimore Orioles and the 2016 Mary Pickersgill Award recipient. “It means a lot to me. I work in sports, a male-dominated field. If I can change the mindset of any person I encounter about women working in predominately male fields, then I truly am carrying on her legacy.”

For Flag Day in June, the museum hosted a naturalization ceremony for 28 new American citizens from 18 countries. Shores Davis says that out of everything the house museum does, introducing school-age kids, who make up almost 60 percent of the site’s more than 11,000 annual visitors, to the house and Pickersgill’s story is one of the most rewarding experiences for her and her team.

“[The museum] shows students how people needed to be resourceful. There are things that we think of as antiquated now, but everyone had a job and everyone had something to do. One of our taglines is that normal people make history,” Shores Davis says. “You’re making history right now by the things you’re doing and learning and participating in. Mary often doesn’t get recognized for her contribution of making the flag, so I think that the house combined with the tour and the objects build a picture of [her]. We don’t know much about her personality, but I think it’s something you can glean when you’re in the home.”